Kolmogorov complexity

In algorithmic information theory (a subfield of computer science), the Kolmogorov complexity of an object, such as a piece of text, is a measure of the computational resources needed to specify the object.

Kolmogorov complexity is also known as descriptive complexity, Kolmogorov-Chaitin complexity, stochastic complexity, algorithmic entropy, or program-size complexity.

For example, consider the following two strings of length 64, each containing only lowercase letters, numbers, and spaces:

abababababababababababababababababababababababababababababababab 4c1j5b2p0cv4w1x8rx2y39umgw5q85s7uraqbjfdppa0q7nieieqe9noc4cvafzf

The first string has a short English-language description, namely "ab 32 times", which consists of 11 characters. The second one has no obvious simple description (using the same character set) other than writing down the string itself, which has 64 characters.

More formally, the complexity of a string is the length of the string's shortest description in some fixed universal description language. The sensitivity of complexity relative to the choice of description language is discussed below. It can be shown that the Kolmogorov complexity of any string cannot be more than a few bytes larger than the length of the string itself. Strings whose Kolmogorov complexity is small relative to the string's size are not considered to be complex. The notion of Kolmogorov complexity is considered surprisingly deep and can be used to state and prove impossibility results akin to Gödel's incompleteness theorem and Turing's halting problem.

Contents |

Definition

To define Kolmogorov complexity, we must first specify a description language for strings. Such a description language can be based on any programming language, such as Lisp, Pascal, or Java Virtual Machine bytecode. If P is a program which outputs a string x, then P is a description of x. The length of the description is just the length of P as a character string. In determining the length of P, the lengths of any subroutines used in P must be accounted for. The length of any integer constant n which occurs in the program P is the number of bits required to represent n, that is (roughly) log2n.

We could alternatively choose an encoding for Turing machines, where an encoding is a function which associates to each Turing Machine M a bitstring <M>. If M is a Turing Machine which on input w outputs string x, then the concatenated string <M> w is a description of x. For theoretical analysis, this approach is more suited for constructing detailed formal proofs and is generally preferred in the research literature. The binary lambda calculus may provide the simplest definition of complexity yet. In this article we will use an informal approach.

Any string s has at least one description, namely the program

function GenerateFixedString()

return s

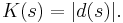

If a description of s, d(s), is of minimal length—i.e. it uses the fewest number of characters—it is called a minimal description of s. Then the length of d(s)—i.e. the number of characters in the description—is the Kolmogorov complexity of s, written K(s). Symbolically,

We now consider how the choice of description language affects the value of K and show that the effect of changing the description language is bounded.

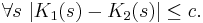

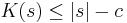

Theorem. If K1 and K2 are the complexity functions relative to description languages L1 and L2, then there is a constant c (which depends only on the languages L1 and L2) such that

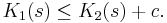

Proof. By symmetry, it suffices to prove that there is some constant c such that for all bitstrings s,

Now, suppose there is a program in the language L1 which acts as an interpreter for L2:

function InterpretLanguage(string p)

where p is a program in L2. The interpreter is characterized by the following property:

- Running InterpretLanguage on input p returns the result of running p.

Thus if P is a program in L2 which is a minimal description of s, then InterpretLanguage(P) returns the string s. The length of this description of s is the sum of

- The length of the program InterpretLanguage, which we can take to be the constant c.

- The length of P which by definition is K2(s).

This proves the desired upper bound.

See also invariance theorem.

History and context

Algorithmic information theory is the area of computer science that studies Kolmogorov complexity and other complexity measures on strings (or other data structures).

The concept and theory of Kolmogorov Complexity is based on a crucial theorem first discovered by Ray Solomonoff who published it in 1960, describing it in "A Preliminary Report on a General Theory of Inductive Inference" (see ref) as part of his invention of Algorithmic Probability. He gave a more complete description in his 1964 publications, "A Formal Theory of Inductive Inference," Part 1 and Part 2 in Information and Control (see ref).

Andrey Kolmogorov later independently published this theorem in Problems Inform. Transmission, 1, (1965), 1-7. Gregory Chaitin also presents this theorem in J. ACM, 16 (1969). Chaitin's paper was submitted October 1966, revised in December 1968 and cites both Solomonoff's and Kolmogorov's papers.

The theorem says that among algorithms that decode strings from their descriptions (codes) there exists an optimal one. This algorithm, for all strings, allows codes as short as allowed by any other algorithm up to an additive constant that depends on the algorithms, but not on the strings themselves. Solomonoff used this algorithm, and the code lengths it allows, to define a string's `universal probability' on which inductive inference of a string's subsequent digits can be based. Kolmogorov used this theorem to define several functions of strings: complexity, randomness, and information.

When Kolmogorov became aware of Solomonoff's work, he acknowledged Solomonoff's priority (IEEE Trans. Inform Theory, 14:5(1968), 662-664). For several years, Solomonoff's work was better known in the Soviet Union than in the Western World. The general consensus in the scientific community, however, was to associate this type of complexity with Kolmogorov, who was concerned with randomness of a sequence while Algorithmic Probability became associated with Solomonoff, who focused on prediction using his invention of the universal a priori probability distribution.

There are several other variants of Kolmogorov complexity or algorithmic information. The most widely used one is based on self-delimiting programs and is mainly due to Leonid Levin (1974).

An axiomatic approach to Kolmogorov complexity based on Blum axioms (Blum 1967) was introduced by Mark Burgin in the paper presented for publication by Andrey Kolmogorov (Burgin 1982). This approach was further developed in the book (Burgin 2005) and applied to software metrics (Burgin and Debnath, 2003; Debnath and Burgin, 2003).

Some consider that naming the concept "Kolmogorov complexity" is an example of the Matthew effect.[1]

Basic results

In the following discussion let K(s) be the complexity of the string s.

It is not hard to see that the minimal description of a string cannot be too much larger than the string itself: the program GenerateFixedString above that outputs s is a fixed amount larger than s.

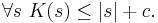

Theorem. There is a constant c such that

Incomputability of Kolmogorov complexity

The first result is that there is no way to effectively compute K.

Theorem. K is not a computable function.

In other words, there is no program which takes a string s as input and produces the integer K(s) as output. We show this by contradiction by making a program that creates a string that should only be able to be created by a longer program. Suppose there is a program

function KolmogorovComplexity(string s)

that takes as input a string s and returns K(s). Now consider the program

function GenerateComplexString(int n)

for i = 1 to infinity:

for each string s of length exactly i

if KolmogorovComplexity(s) >= n

return s

quit

This program calls KolmogorovComplexity as a subroutine. This program tries every string, starting with the shortest, until it finds a string with complexity at least n, then returns that string. Therefore, given any positive integer n, it produces a string with Kolmogorov complexity at least as great as n. The program itself has a fixed length U. The input to the program GenerateComplexString is an integer n; here, the size of n is measured by the number of bits required to represent n which is log2(n). Now consider the following program:

function GenerateParadoxicalString()

return GenerateComplexString(n0)

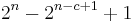

This program calls GenerateComplexString as a subroutine and also has a free parameter n0. This program outputs a string s whose complexity is at least n0. By an auspicious choice of the parameter n0 we will arrive at a contradiction. To choose this value, note s is described by the program GenerateParadoxicalString whose length is at most

where C is the "overhead" added by the program GenerateParadoxicalString. Since n grows faster than log2(n), there exists a value n0 such that

But this contradicts the definition of having a complexity at least n0. That is, by the definition of K(s), the string s returned by GenerateParadoxicalString is only supposed to be able to be generated by a program of length n0 or longer, but GenerateParadoxicalString is shorter than n0. Thus the program named "KolmogorovComplexity" cannot actually computably find the complexity of arbitrary strings.

This is proof by contradiction where the contradiction is similar to the Berry paradox: "Let n be the smallest positive integer that cannot be defined in fewer than twenty English words." It is also possible to show the uncomputability of K by reduction from the uncomputability of the halting problem H, since K and H are Turing-equivalent.[1]

In the programming languages community there is a corollary known as the Full employment theorem, stating there is no perfect size-optimizing compiler.

Chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity

The chain rule for Kolmogorov complexity states that

It states that the shortest program that reproduces X and Y is no more than a logarithmic term larger than a program to reproduce X and a program to reproduce Y given X. Using this statement one can define an analogue of mutual information for Kolmogorov complexity.

Compression

It is straightforward to compute upper bounds for  : simply compress the string

: simply compress the string  with some method, implement the corresponding decompressor in the chosen language, concatenate the decompressor to the compressed string, and measure the resulting string's length.

with some method, implement the corresponding decompressor in the chosen language, concatenate the decompressor to the compressed string, and measure the resulting string's length.

A string s is compressible by a number c if it has a description whose length does not exceed  . This is equivalent to saying

. This is equivalent to saying  . Otherwise s is incompressible by c. A string incompressible by 1 is said to be simply incompressible; by the pigeonhole principle, incompressible strings must exist, since there are

. Otherwise s is incompressible by c. A string incompressible by 1 is said to be simply incompressible; by the pigeonhole principle, incompressible strings must exist, since there are  bit strings of length n but only

bit strings of length n but only  shorter strings, that is strings of length

shorter strings, that is strings of length  or less.

or less.

For the same reason, most strings are complex in the sense that they cannot be significantly compressed:  is not much smaller than

is not much smaller than  , the length of s in bits. To make this precise, fix a value of n. There are

, the length of s in bits. To make this precise, fix a value of n. There are  bitstrings of length n. The uniform probability distribution on the space of these bitstrings assigns exactly equal weight

bitstrings of length n. The uniform probability distribution on the space of these bitstrings assigns exactly equal weight  to each string of length n.

to each string of length n.

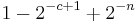

Theorem. With the uniform probability distribution on the space of bitstrings of length n, the probability that a string is incompressible by c is at least  .

.

To prove the theorem, note that the number of descriptions of length not exceeding  is given by the geometric series:

is given by the geometric series:

There remain at least

many bitstrings of length n that are incompressible by c. To determine the probability divide by  .

.

This theorem is the justification for various challenges in comp.compression FAQ. Despite this result, it is sometimes claimed by certain individuals (considered cranks) that they have produced algorithms which uniformly compress data without loss. See lossless data compression.

Chaitin's incompleteness theorem

We know that, in the set of all possible strings, most strings are complex in the sense that they cannot be described in any significantly "compressed" way. However, it turns out that the fact that a specific string is complex cannot be formally proved, if the string's complexity is above a certain threshold. The precise formalization is as follows. First fix a particular axiomatic system S for the natural numbers. The axiomatic system has to be powerful enough so that to certain assertions A about complexity of strings one can associate a formula FA in S. This association must have the following property: if FA is provable from the axioms of S, then the corresponding assertion A is true. This "formalization" can be achieved either by an artificial encoding such as a Gödel numbering or by a formalization which more clearly respects the intended interpretation of S.

Theorem. There exists a constant L (which only depends on the particular axiomatic system and the choice of description language) such that there does not exist a string s for which the statement

(as formalized in S) can be proven within the axiomatic system S.

Note that by the abundance of nearly incompressible strings, the vast majority of those statements must be true.

The proof of this result is modeled on a self-referential construction used in Berry's paradox. The proof is by contradiction. If the theorem were false, then

- Assumption (X): For any integer n there exists a string s for which there is a proof in S of the formula "K(s) ≥ n" (which we assume can be formalized in S).

We can find an effective enumeration of all the formal proofs in S by some procedure

function NthProof(int n)

which takes as input n and outputs some proof. This function enumerates all proofs. Some of these are proofs for formulas we do not care about here (examples of proofs which will be listed by the procedure NthProof are the various known proofs of the law of quadratic reciprocity, those of Fermat's little theorem or the proof of Fermat's last theorem all translated into the formal language of S). Some of these are complexity formulas of the form K(s) ≥ n where s and n are constants in the language of S. There is a program

function NthProofProvesComplexityFormula(int n)

which determines whether the nth proof actually proves a complexity formula K(s) ≥ L. The strings s and the integer L in turn are computable by programs:

function StringNthProof(int n)

function ComplexityLowerBoundNthProof(int n)

Consider the following program

function GenerateProvablyComplexString(int n)

for i = 1 to infinity:

if NthProofProvesComplexityFormula(i) and ComplexityLowerBoundNthProof(i) ≥ n

return StringNthProof(i)

quit

Given an n, this program tries every proof until it finds a string and a proof in the formal system S of the formula K(s) ≥ L for some L ≥ n. The program terminates by our Assumption (X). Now this program has a length U. There is an integer n0 such that U + log2(n0) + C < n0, where C is the overhead cost of

function GenerateProvablyParadoxicalString()

return GenerateProvablyComplexString(n0)

quit

The program GenerateProvablyParadoxicalString outputs a string s for which there exists an L such that K(s) ≥ L can be formally proved in S with L ≥ n0. In particular K(s) ≥ n0 is true. However, s is also described by a program of length U + log2(n0) + C so its complexity is less than n0. This contradiction proves Assumption (X) cannot hold.

Similar ideas are used to prove the properties of Chaitin's constant.

Minimum message length

The minimum message length principle of statistical and inductive inference and machine learning was developed by C.S. Wallace and D.M. Boulton in 1968. MML is Bayesian (it incorporates prior beliefs) and information-theoretic. It has the desirable properties of statistical invariance (the inference transforms with a re-parametrisation, such as from polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates), statistical consistency (even for very hard problems, MML will converge to any underlying model) and efficiency (the MML model will converge to any true underlying model about as quickly as is possible). C.S. Wallace and D.L. Dowe (1999) showed a formal connection between MML and algorithmic information theory (or Kolmogorov complexity).

Kolmogorov randomness

Kolmogorov randomness (also called algorithmic randomness) defines a string (usually of bits) as being random if and only if it is shorter than any computer program that can produce that string. This definition of randomness is critically dependent on the definition of Kolmogorov complexity. To make this definition complete, a computer has to be specified, usually a Turing machine. According to the above definition of randomness, a random string is also an "incompressible" string, in the sense that it is impossible to give a representation of the string using a program whose length is shorter than the length of the string itself. However, according to this definition, most strings shorter than a certain length end up to be (Chaitin-Kolmogorovically) random because the best one can do with very small strings is to write a program that simply prints these strings.

See also

- Data compression

- Inductive inference

- Kolmogorov structure function

- Important publications in algorithmic information theory

- Levenshtein distance

- Grammar induction

References

- Blum, M. (1967), "On the Size of Machines", Information and Control, v. 11, pp. 257–265.

- Burgin, M. (1982), "Generalized Kolmogorov complexity and duality in theory of computations", Notices of the Russian Academy of Sciences, v.25, No. 3, pp. 19–23.

- Mark Burgin (2005), Super-recursive algorithms, Monographs in computer science, Springer.

- Burgin, M. and Debnath, N. "Hardship of Program Utilization and User-Friendly Software", in Proceedings of the International Conference “Computer Applications in Industry and Engineering”, Las Vegas, Nevada, 2003, pp. 314–317.

- Cover, Thomas M. and Thomas, Joy A., Elements of information theory, 1st Edition. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1991. ISBN 0-471-06259-6. 2nd Edition. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 2006. ISBN 0-471-24195-4.

- Debnath, N.C. and Burgin, M. (2003), "Software Metrics from the Algorithmic Perspective", in Proceedings of the ISCA 18th International Conference “Computers and their Applications”, Honolulu, Hawaii, pp. 279–282.

- Kolmogorov, Andrei N. (1963). "On Tables of Random Numbers". Sankhyā Ser. A. 25: pp. 369–375. MR178484

- Kolmogorov, Andrei N. (1998). "On Tables of Random Numbers". Theoretical Computer Science 207 (2): pp. 387--395. doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(98)00075-9. MR1643414

- Lajos, Rónyai and Gábor, Ivanyos and Réka, Szabó, Algoritmusok. TypoTeX, 1999. ISBN 963-2790-14-6

- Solomonoff, Ray, "A Preliminary Report on a General Theory of Inductive Inference", Report V-131, Zator Co., Cambridge, Ma. Feb 4, 1960, revision, Nov., 1960.

- Solomonoff, Ray, "A Formal Theory of Inductive Inference", Information and Control, Part I, Vol 7, No. 1 pp 1–22, March 1964 and Part II, Vol 7, No. 2 pp 224–254, June 1964.

- Li, Ming and Vitányi, Paul, An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, Springer, 1997. Introduction chapter full-text.

- Yu Manin, A Course in Mathematical Logic, Springer-Verlag, 1977.

- Sipser, Michael, Introduction to the Theory of Computation, PWS Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0-534-95097-3.

- Wallace, C. S. and Dowe, D. L., Minimum Message Length and Kolmogorov Complexity, Computer Journal, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1999).

External links

- The Legacy of Andrei Nikolaevich Kolmogorov

- Chaitin's online publications

- Solomonoff's IDSIA page

- Generalizations of algorithmic information by J. Schmidhuber

- Ming Li and Paul Vitanyi, An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and Its Applications, 2nd Edition, Springer Verlag, 1997.

- Tromp's lambda calculus computer model offers a concrete definition of K()

- Universal AI based on Kolmogorov Complexity ISBN 3-540-22139-5 by M. Hutter: ISBN 3-540-22139-5

- David Dowe's Minimum Message Length (MML) and Occam's razor pages.

- P. Grunwald, M. A. Pitt and I. J. Myung (ed.), Advances in Minimum Description Length: Theory and Applications, M.I.T. Press, April 2005, ISBN 0-262-07262-9.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||